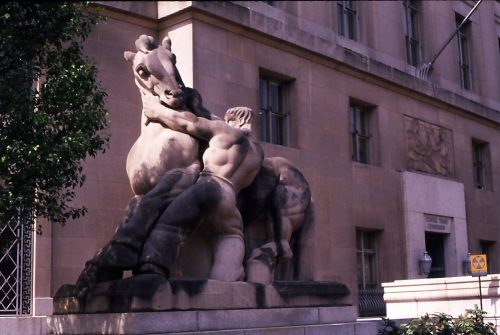

This 1942 sculpture by Michael Lantz, 17-feet long, is meant to suggest a heroic figure (the FTC) restraining violent and untamed American commerce.

Author: Steven Levitsky

If you liked the old computer game, “Minesweeper,” then you’re ready to take on Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) filings for antitrust review of mergers & acquisitions. Both have rules. And both can produce unexpected catastrophes even if you think you’re following the rules. In fact, major clients, advised by major law firms, have been hit with hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines for mistakes that no one thought of at the time.

Let’s start with the 50,000 foot view of HSR compliance. You might know the basics: (a) you need to make an HSR filing when one side of the transaction has sales or assets of at least $16.9 million; (b) the other side has sales or assets of at least $168.8 million; (c) the transaction size is greater than $84.4 million; and (d) no exemptions apply. (These are 2018 figures).

An example to consider

Here’s an example of how things can work out badly. Let’s assume you get a call from the CEO of your client, Alpha Co. Alpha Co. is a small and relatively new company and the CEO tells you:

- Alpha’s annual sales and assets are $15 million.

- Alpha plans to buy $80 million of the voting securities of Bravo Ltd. (Alpha’s borrowing $65 million to do the deal.)

- Based on this, he wants to know if they need to make an HSR filing.

Applying what you know, you conclude that the “size-of-person” and “size-of-transaction” tests are both not met, so no HSR filing is required. Alpha Co. goes ahead and closes the deal.

Three months later, your client hears from the FTC. The FTC tells them that they violated the HSR Act by not filing, and that the fine is $41,484 per day, or $3,733,560 in all. What went wrong? (We’ll explain in detail in Point 2.)

But generally, what went wrong is that the 50,000 foot view is not enough. HSR rules are extremely technical and, some would say, not exactly logical. A lot of HSR terms don’t have a common sense meaning. You need to check and cross-reference the definitions and rules. And these, by the way, are not organized in any friendly or rational way, but seem to read like the Tax Code.

Here are some basic HSR concepts that might help you avoid the worst minefields.

- What are the basic HSR tests?

There are two tests to see if a filing is required.

First, “size-of-person.” Normally, you don’t need to file for the antitrust enforcers unless one side of the deal has sales or assets of at least $16.9 million and the other side has sales or assets of at least $168.8 million. (This are 2018 figures; these numbers change every February.)

But, as we’ll see soon in Point 2, the size-of-person test does not mean the size of the transaction party. Instead, it means the size of the buyer’s entire business group, or everything under the control of its highest entity (see §5). Don’t fall into the trap of measuring an incomplete control group.

Second, the “size-of-transaction” must be over $84.4 million (again, this is 2018; the numbers change every February). But there are several other filing thresholds that cover more purchases in the same target and could require successive filings. These include $168.8 million; $843.9 million; 25% of the target — but only if the size-of-transaction is more than $1.688 million; and 50% of the target — or control. Once you get control, you can buy as much more of the target as you want without ever filing again.

But, as we’ll see soon in Point 2, the “size-of-transaction” does not really mean the size of the transaction. Instead, it means (1) the combination of existing holdings and planned acquisitions, (2) that the entire buyer control group will have in the target control group after the deal closes (see §2). This includes voting stock acquired years before, that has to be analyzed at its current value. Don’t fall into the trap of measuring the wrong amount.

- What is an “ultimate parent entity” and why does it matter?

The “ultimate parent entity” is the top controlling entity of an entire business group.

The “ultimate parent entity” matters to your antitrust filing for the following reason. The purpose of the HSR filing system is to let the antitrust agencies know of significant shifts in competitive power. As a result, they don’t care about the names on the contract, which may be only small subs or special purpose vehicles. The antitrust agencies want to know what is really happening in terms of changes of competitive power.

To give the agencies that information, you must identify the entire control group of your transaction party. You do this by tracing control upwards from the transaction party (Alpha Co., in our case) to the very highest control level of the business group. That entity at the top, that isn’t controlled by anyone else, is the “ultimate parent entity,” which can be a company or an individual. The “ultimate parent entity” makes the filing. Its collective size and holdings affect the “size-of-person” and “size-of-transaction” tests we discussed in Point 1.

Continue reading →

The Antitrust Attorney Blog

The Antitrust Attorney Blog